Text: Eva Fernández Martin Illustration: Sergio Ortiz Borbolla

Cocaine

Cocaine is a highly addictive stimulant drug that acts directly on the central nervous system. It increases brain activity by raising energy levels and alertness through short-lived feelings of euphoria. Its main chemical substance comes from the leaves of the coca plant Erythroxylum, which contains varying levels of the alkaloid. Although the cocaine alkaloid content of the coca leaf is between 0.5 and 1.0 percent, the United Nations declared the plant illegal. However, millions of people in Latin America use it as a mild stimulant, hunger suppressant, and to combat fatigue and altitude sickness.

Cocaine constricts blood vessels, increases body temperature, blood pressure and heart rate, and can cause serious adverse effects, particularly when combined with other substances. It is so addictive that in experiments, laboratory mice endure electric shocks and even give up food and water in order to get it. Sustained use over time kills dopamine receptors, our “pleasure centres”, which means that more doses are needed to generate the same effect.

Cocaine is mainly produced in clandestine laboratories in countries including Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, where the climatic conditions and altitude of the Andes provide the perfect environment for the cultivation of the coca plant, although criminal organisations have been trying to establish laboratories in other areas.

The cocaine trade is controlled by complex criminal organisations, mainly Colombian and Mexican, which lead the production, transport and distribution of the drug globally. These organisations operate with a high degree of sophistication and adaptability, using distribution networks and collaborators in multiple countries. At the local level, hundreds of thousands of people are involved in activities related to the cultivation, processing and transport of drugs, including cocaine, many of whom come from marginalised communities and are vulnerable to violence and exploitation. Despite the authorities’ efforts to combat cocaine trafficking, consumption of the drug continues to increase worldwide, especially in the Americas, Europe and Oceania.

A long (and complex) history

3,500 Years Ago:

The history of cocaine begins thousands of years ago in what is now the Andes region of South America, where indigenous peoples cultivated the coca plant for its stimulant properties. The Inca civilisation, in particular, revered the coca leaf, using it in religious ceremonies and as a form of currency. In fact, the word “coca” comes from the indigenous Aymara language.

16th century:

The arrival of the Spanish conquistadors radically changed the perception of coca from being revered to being demonised as the “Devil’s Agent“. However, they soon recognised the economic value of the plant, and began to use it as a means of payment for indigenous workers. This led to the exploitation and commercialisation of coca by European countries, laying the groundwork for its eventual global distribution.

19th century:

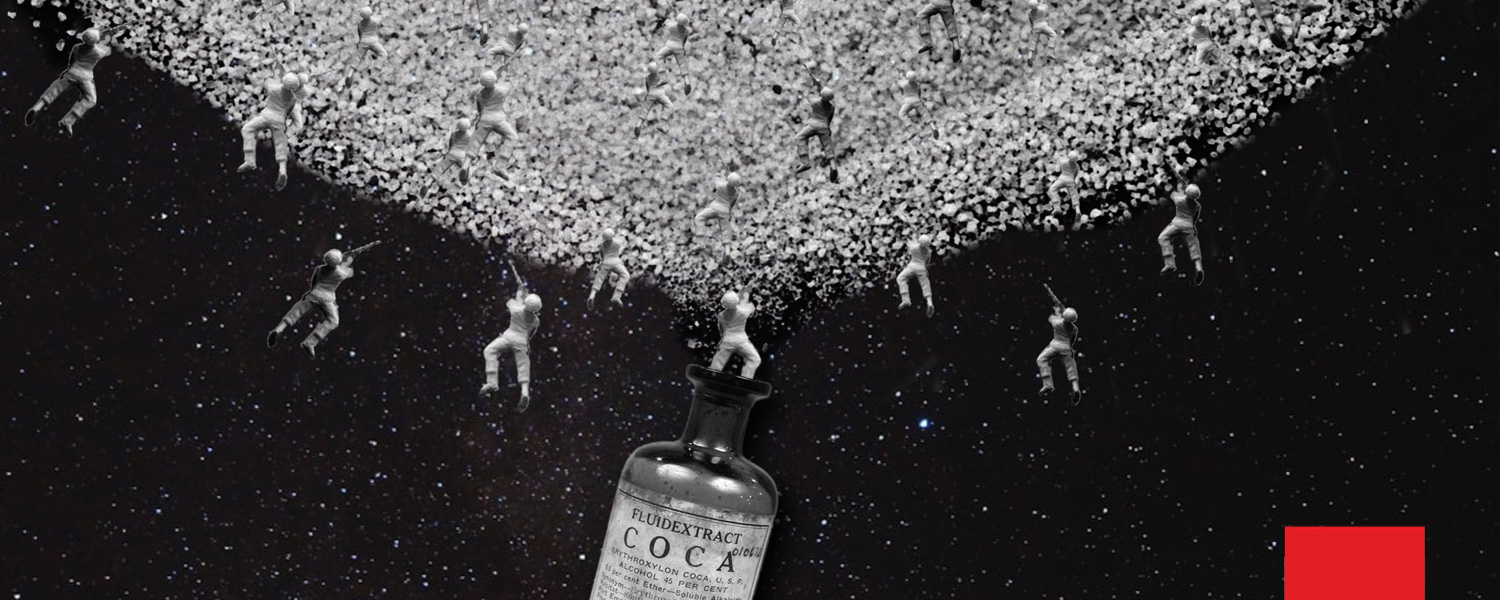

The 19th century saw significant advances in the isolation and synthesis of psychoactive compounds from a number of plants, including at the hands of German chemist Friedrich Gaedcke, who succeeded in isolating the alkaloid cocaine from coca leaves, thus laying the foundation for its medical use. The discovery was a furore. In fact, leading figures such as Sigmund Freud became fans and helped popularise its use.

1880s:

Cocaine enjoyed a brief period of widespread acceptance, with medical professionals prescribing it for a wide range of ailments, from depression to toothaches. It even found its way into the original recipe for popular drinks such as Coca-Cola. But the spell was short-lived, and as soon as concerns began to emerge about its addictive properties and the harmful effects its use caused, public perception changed.

1960-1970:

Once the criticism began, it hardly stopped. Medical associations and governments began to heavily regulate its distribution. In 1961, the first international rules to regulate the availability of narcotic and psychedelic drugs, including cocaine, were established at the United Nations. The United States, under the leadership of President Nixon, launched what they called the “War on Drugs” in 1971, ushering in a new era of prohibition and criminalisation.

1980s:

But in parallel to the many prohibitions, cocaine’s popularity exploded. In fact, the white powder is said to have been the gasoline that ran the machine of excess and glamour, especially in Western societies in the 1980s. It became synonymous with the hedonistic culture of the time, fuelling a lucrative illicit trade. The emergence of crack, a cheaper and more potent form of the drug, had devastating consequences, especially in marginalised communities.

Global Challenges

Despite efforts to combat cocaine use, its availability and consumption continue to increase, challenging the effectiveness of current strategies. The controversial “war on drugs“, initiated by President Nixon in 1971, has been widely criticised for its punitive approach and disproportionate impacts on ethnic minorities and marginalised communities.

These policies have failed to significantly reduce the supply of cocaine on the global market. Moreover, mass incarceration measures, even for small-scale trafficking offences, have overwhelmed prison systems and contributed to the stigmatisation and marginalisation of vulnerable groups.

Within the framework of the United Nations, regulations have been established to regulate the control of narcotic and psychedelic drugs, under the supervision of the International Narcotics Control Board. However, cocaine prohibition policies vary significantly from country to country. For example, coca leaves have a special cultural status in Bolivia and Peru, while in Saudi Arabia, possession, transport or consumption of drugs are punished by death. On the other hand, countries such as Argentina, Brazil and Colombia have opted to decriminalise private consumption, although they continue to combat its commercialisation.

The drug policy debate is constantly evolving, with an increasing emphasis on social justice and public health. Some countries have explored alternative approaches, such as regulation and harm reduction strategies, recognising the limitations of traditional prohibitionist policies. Examples such as Portugal, which has decriminalised personal possession of hard drugs, have shown significant decreases in overdose deaths and HIV cases related to drug use. However, this approach faces challenges in terms of implementation and public acceptance.

The legalisation and regulation of certain drugs has been presented as an option to address the problems associated with the black market and criminality. Proponents of legalisation argue that the creation of legal markets could benefit marginalised communities and reduce the power of criminal organisations. However, the path towards fairer and more equitable regulation remains a challenge, as current models may not adequately address existing inequalities.

As drug policies around the world evolve, the need for more public health and social welfare-focused approaches, addressing the underlying causes of problematic drug use and promoting alternatives based on evidence and respect for human rights, is evident. The fight against cocaine, and drugs in general, requires a comprehensive and collaborative approach between governments, international organisations and civil society. There are no simple solutions to complex challenges.