Text: Ronna Rísquez, Lorena Meléndez, Sheyla Urdaneta, Liz Gascón and Ahiana Figueroa*.

*This article is part of a special investigation by El Espectador and Alianza Rebelde Investiga (Runrun.es, El Pitazo and Tal Cual), and it is being reprinted with permission. You can visit the original stories, which have been nominated to the Gabo journalism award, here.

Venezuela is considered the paradise of beauty pageants. It is home to Miss Universes, six Miss Worlds and a dozen other queens from various international competitions. This is why, it is a common joke that the second export “product” of the South American country, after oil, is beautiful women.

Today, some of these competitions are used to recruit hundreds of Venezuelan women and girls, who are transported as “merchandise” throughout Latin America by trafficking networks. At the top of this structure of sexual exploitation is the criminal gang Tren de Aragua.

“Among the events promoted by the criminal gang (the Tren de Aragua) in the city of Güiria are beauty contests. In these contests, the girls who win the first three places receive prizes such as mobile phones, money and other things. This is how the recruitment process for trafficking begins,” said Magaly*, an activist who provides support to survivors of trafficking, and who asked not to reveal her identity for fear of reprisals.

“Then they invite them to parties, even in the Tocorón prison (located in the centre of Venezuela, where Héctor Rusthenford Guerrero, or Niño Guerrero, the leader of the Tren de Aragua, is still imprisoned),” the activist explained.

Güiria is the capital of the Valdez municipality, a city of 40,000 inhabitants, located in the eastern Venezuelan state of Sucre. It had an important fishing industry and was very prosperous until the early 2000s. Its strategic location facilitates the transport of all kinds of goods by sea to the Caribbean, Europe and Africa.

Between 2017 and 2018, while many of its inhabitants were fleeing the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela on precarious fishing boats bound for Trinidad and Tobago, people, including members of the Tren de Aragua, travelled to the area and settled in nearby villages. “You recognise them by the clothes they wear, the way they talk and the weapons some of them carry, like rifles. Everyone in town knows that one of the pranes (imprisoned crime bosses) is from here, from Güiria,” explained Juan Carlos*, a local shopkeeper who knows how the trafficking business operates and who –like everyone in town– knows that Carlos López, or “Pilo”, who is also a local, is one of the criminal bosses in the Aragua Penitentiary Centre.

The Tren quickly took control of all criminal activity in and around the small town. This included the trafficking of women for sexual exploitation, one of more than 20 illicit economies the criminal group has dabbled in since its birth in 2014. “The girls are manipulated, romanced and forced into sex work. They capture them with beauty contests. Here there are beauty contests every month,” said Juan Carlos.

Pranes started trafficking women at the end of the first decade of the 2000s, when the authorities allowed family members and partners of prisoners to stay overnight. These visitors stayed for weeks and months, and sex workers also started entering the prisons.

Tocorón became an attractive destination for sex work: there were parties, money and security. But not all of them arrived at the prison by their own means and not all of them were of legal age. “There are people in the neighbourhoods and in the villages who work for the Tren de Aragua and were in charge of recruiting teenage girls. Points have also been set up in some of the squares in Maracay where vehicles arrive to pick them up and take them to Tocorón,” an official who works for the state security forces explained.

The Tren de Aragua began exporting this crime in 2017, during the worst years of Venezuela’s humanitarian emergency, when millions of people began fleeing the country. A judicial police official, who asked for her name not to be published, explained that it was during this period that complaints and arrests associated with trafficking for sexual exploitation began to increase dramatically. “In those years there was a lot of desperation due to the economic crisis and young women were easily captured by these networks, particularly by the Aragua Train,” she explained.

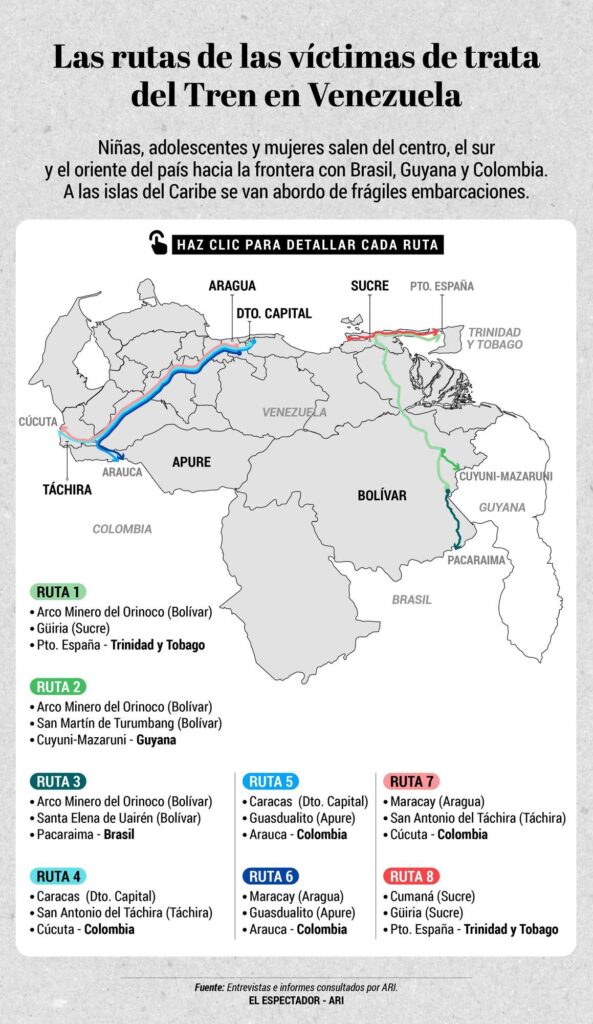

It was at this time that the crime group began its national and international expansion that now includes operations in Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and has Colombia as its base of operations.

In Venezuela, human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation is a crime that has been on the rise, with no official data or action by the State to stop it. In 2004, the US State Department’s Annual Report on Trafficking in Persons placed Venezuela in the third category of countries whose governments do not fully comply with the minimum standards established in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) and are not making significant efforts to achieve them. It remained in that category until the 2022 report, which noted that efforts to curb this crime had not shown results. From 24 mentions of Venezuela in the 2004 report, the number rose to 125 in the 2022 report, indicating an increase in cases and international concern.

According to press coverage,

Between 2022 and 2023, there is information of cases of recruitment and trafficking of women, girls and adolescents in at least 10 of Venezuela’s 23 departments: Aragua, Bolívar, Falcón, Monagas, Mérida, Apure, Táchira, Carabobo, Distrito Capital (Caracas) and Sucre, according to press reports.

Beauty pageants and modelling agencies

When the Train de Aragua arrived in Güiria, on the coast of Sucre, one of the activities it popularised in the town were beauty pageants. Even in 2018, when the country was going through one of the worst economic, political and social crises, a large party was organised to elect a Carnival queen.

The people behind the beauty pageants, who are linked to the Tren de Aragua, earned the trust of the local community so “when the women realise what is happening the trafficked relationship has already been established,” said Magaly, the activist who helps the victims.

Juan Carlos added that, in some cases, they also use modelling agencies for girls and adolescents as a front. There are accounts on social networks in which 15, 16 and 17-year-old girls from Güiria invite other girls to join these agencies and sign up for the beauty pageants. One of the messages from a girl in a promotional video reads: “I want all those girls who have the desire to move forward to fight for their dreams, because just as I am doing it, many of us can.”

“They are girls who have economic needs and are in charge of promoting the recruitment of other young girls for prostitution, first in the prison itself, then outside of it and especially in Trinidad,” said Juan Carlos. Some of them fall in love with the gang members, become their girlfriends and are then manipulated into joining the “business”, Magaly added.

“Many of the people who are smuggled are also victims of trafficking, but they are criminalised. In Trinidad and Tobago, there is tourism and sexual exploitation. It is believed that some missing persons may be in these places, but there has not been a thorough investigation into any of it,” said Norma Ferrer of the NGO Corporazione Internazionale (COOPI).

Trafficking victims include women of all ages: 20, 30, 40 years old. In these cases, when they travel to Trinidad and Tobago, the women are informed that they must pay a fee in dollars to the gang for the “help” of taking them to the island on a boat that leaves from Güiria. There, someone who is part of the network received them and, after being initiated into sex work, they are told they must pay a debt of approximately 2,000 dollars, before they are set free. However, due to their irregular migration status, they are left with little choice but to continue as sex workers.

The Tren de Aragua also sells Venezuelan teenage girls to criminal organisations in Trinidad and Tobago. They do not charge them for the boat fare, but hand them over to other trafficking networks in exchange for US$ 300 or 500, according to another person consulted for this story.

Norma Ferrer, from the NGO COOPI, explained that the forms of recruitment do not always involve networks dedicated to human trafficking. “We have seen a lot of family members, mothers, uncles, uncles, cousins who sell their family members.”

The shipwreck of three boats (Ave María, Yonaily and Mi Refugio) that had left the coast of Güiria between 2019 and 2020 left more than 100 migrants dead, including many women and girls, who were being taken to Trinidad and Tobago to be sexually exploited.

“In those boats were underage girls who had run away from home, encouraged by their schoolmates. They would take them to hotels, prepare them, and buy them clothes. Then they would take them on the trips,” said a lawyer from Güiria, who was familiar with the stories of some of the victims.

Even though the police have carried out several operations in Sucre, in which they arrested a number of people for human trafficking, they have reported little about the gangs involved. Humanitarian organisations, such as Caritas Venezuela, helped 36 women in Güiria who were victims of this crime and were deported in 2022.

Out of 1,390 Venezuelan women rescued from trafficking networks in the region in 2022 (of whom 284 were girls and adolescents), seven came from Trinidad and Tobago, according to the report “Free and Safe” from the organisation Mulier.

The inhabitants of the Paria Peninsula claim that the Tren de Aragua have extended their control in the area. Its connections reach not only Trinidad, but also Grenada, Martinique, Barbados and Saint Lucia (coincidentally, countries that benefit from energy cooperation deals with Venezuela). “Nothing leaves here without the approval of the Aragua Train,” said Juan Carlos.

Although there are no official figures that illustrate the true extent of human trafficking, the opening, in September 2022, of an office exclusively dedicated to this crime within the scientific police, is an indicator of the growth of this illicit economy and the concern it has generated in the authorities.

“Those people are the devil”

“‘You think I’m playing games? You’ll see what it’s like. You come with us or your people die. Do you understand me?” That was the last message Ana* received before fleeing her hometown, La Vela de Coro, in Falcón, a coastal state in western Venezuela bordering the islands of Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire.

When they first called her she thought it was a game. “We are from the Tren de Aragua,” the message read “ ‘Tren de Aragua’”, I asked myself, and I said to myself ‘those people made a mistake. What do they want with me?” She assumed it was a friend she had in the orchestra where she took music lessons and joked that he belonged to a gang.

The instructions, however, were clear: “We want you, you come with us, you’ll get your money and you can send some to your family.” From the get go she said she couldn’t, that she wasn’t interested. That’s why the end of the call was blunt: “You don’t understand, or do you want to die?”

One day she was sent a photo on WhatsApp of her walking with her sister in La Vela de Coro square. She remembers that she looked everywhere and saw no one. That day she felt paralysed.

She wrote to a friend and told her about the messages. She was the first person to tell her about the proposal, the threat and the fear. Her friend told her that these men were not playing games, that they were capable of doing what they told her. Her friend knew this because she was living in Curaçao and had already experienced the same thing. Although her friend was prey to another trafficking organisation, she knew about the way the Tren de Aragua operated.

Ana is safe. At least that’s how she feels at the moment. She does not want to give her real name and she is afraid to talk about the dates of the calls. She says that any information could give her away. “You could call me Ana,” she said in an interview for this investigation. Ana had just turned 21, graduated from high school, but was unable to continue her studies. She worked in jewellery shops, in hairdressing salons and had completed a course to do eyebrow lamination and eyelashes. At home, she, her mother and grandmother worked because her little sister was still in high school, she had just turned 15.

She recalls that when her friend asked her to go to Curaçao in the “rapids”, which are motor boats that take people irregularly from La Vela de Coro to the island, she did not want to go. “I’m afraid of all that. My friend told me that I was pretty, that I have a good body, that she had shown a photo of me to people and they liked me. I said no. Other friends did leave.

Since 2019, residents of La Vela de Coro have been talking about the Tren de Aragua, but almost in secret. Ana thought they were just looking for people to kill and threaten, as she had seen on TikTok, and that they had all gone to Peru. But when they told her they wanted her with them, she didn’t quite understand what it was all about. “That’s what they wanted me for, to be a prostitute”.

La Vela de Coro has been in the news in Venezuela since 2017 for the disappearance of people and allegations of trafficking of women for sexual exploitation on the journey that takes them from a town in Falcón state to Curaçao and Aruba. In 2018, an accident that made the “route of death”, as some called it, more visible, took place. A boat with 30 people was shipwrecked. After that accident it became known that it was a business that was dominated by a local gang called Los Lobos and consisted of taking people to Curaçao irregularly.

But when the men of the Tren de Aragua learned of the event, they saw it as a business opportunity, and the fight for it began. “They finished off Los Lobos. Now they are the lords and masters. The women are the ones most at risk,” said Aníbal*, who found out about this practice some time later.

Some of Ana’s friends and high school classmates were preparing to go to work on the island as “models”. Some came back and said that the jobs were as sex workers. “They came back changed, with money, hair extensions, fine clothes and fashionable shoes. They would go and come back to find other women”.

For now, Ana says she is safe. She doesn’t want to know anything about what is or isn’t going on in her village. “I want to ignore everything. Why play with fire. These people are the devil.”

“I want some chicks”

In the case of Aragua state, the Tren de Aragua’s base of operations located in the centre of Venezuela, the recruitment of women for prostitution is constant and wildly extended. “I want some chicks,” is often the phrase with which pranes demand that their external contacts take girls or adolescents to the Tocorón prison.

In Maracay, the capital of Aragua, the area of Las Delicias is used to recruit young girls and the same happens in San Vicente, the community that has been controlled by the Tren de Aragua since 2015. Caña de azúcar and La Candelaria, two urbanisations in the north of the city, are areas where teenage girls and trafficked women are held captive and then taken abroad. Outside the city, these captivity points are in the municipalities of Francisco Linares Alcántara (Santa Rita), Sucre (Cagua) and Zamora (Villa de Cura).

“Chicks” (pollitas) is the name used by the gang to refer to the girls and adolescents. Those they recruit, said a police official, are usually other minors or young people who become friends or boyfriends of the victims in order to convince them to leave the country. In other cases, he said, it is the mothers who hand over their daughters for “forced sex work” he said.

During the first days of March 2023, the Scientific, Criminal and Criminalistic Investigations Corps (CICPC) issued a yellow alert to the International Police (Interpol), a notice issued to find the whereabouts of missing persons. The activation occurred because of a victim of trafficking: a 16-year-old girl last seen on the bus terminal in Maracay, Aragua state.

According to an official report, the investigation began after the girl’s mother reported her disappearance and told police that she had found a conversation on her daughter’s Facebook profile with a woman offering her a job in Peru.

Investigations identified Biesney José Ocanto López, a 33-year-old man, as the person responsible for taking the teenager on board a bus that took her to Guasdualito, Apure state, on the southern border with Colombia. Once there, other members of his criminal group would take the girl to Arauca, to continue her journey to Peru, where she would be sexually exploited.

Ocanto López, arrested in the Santa Rita parish of Maracay is, according to the police, a member of a gang called “Los tratantes internacionales”, a criminal organisation that has never been mentioned in official statements or in the media, and which allegedly operates from the terminals of La Bandera (Distrito Capital), Maracay and Guasdualito.

Although official reports do not indicate a possible link between the detainee and the Tren de Aragua, two police officers interviewed for this investigation stated that there is no way for a criminal group to commit crimes in Aragua without being part of the Tren. “All crime here, in this state, is controlled by them, the pranes of Tocorón”, said a CICPC commissioner in Maracay, who asked not to be named.

Another official from the same institution, who also asked for their identity to be withheld, as they are not authorised to make statements, added that “the only way for a criminal group to commit crimes in Aragua is to pay a ‘vacuna’ – a kind of quota or tax – to the Tren de Aragua. It’s like that, or something like that, because the train goes everywhere,” he said.

On the other hand, it is unlikely that any criminal organisation would decide to operate from Santa Rita, the town where Ocanto López was captured, as this is the town where Héctor Guerrero, or “Niño Guerrero”, the gang leader who operates from the Tocorón prison, was born and raised.

The disappearance of the 16-year-old girl was not the only recent case of human trafficking in Aragua. During February 2023 alone, the state was the scene of at least three other police operations that resulted in people being charged with this crime.

In February, a 22-year-old man was reportedly arrested for allegedly transporting young women recruited through social networks to the border to be sexually exploited in Peru. For each victim transported, the man received US$150. That same month, the CICPC announced the rescue of another alleged victim of trafficking at the Maracay terminal: a 14-year-old girl from the state of Mérida, in the Venezuelan Andean mountain range, who had been lured by a job offer from a woman in the centre of the country. The Tren was not mentioned in this case either, but the stop at Aragua’s main bus terminal does not seem coincidental.

Meanwhile, in Táchira, on the border with Colombia, five young men allegedly members of the Tren de Aragua were arrested for human trafficking and smuggling. The statement by the commander of the Bolivarian National Police (PNB) in that state, Manuel Romero Inciarte, confirmed that it is one of the points of origin of human trafficking in the country: “They capture them in the centre of the country or in Caracas. They charge them US$120 and promise them logistical facilities. They lock them up in hotels or in residences, take them through trails and abandon them on the other side”. However, testimonies gathered for this investigation in Colombia, Peru and Chile affirmed that this “abandonment” does not occur; the Tren de Aragua takes the victims to different destinations to sexually exploit them.

A CICPC detective in Aragua corroborated the rise of crime in the region: “Now it is strong. People fall for lack of money and desperation. They also use them to traffic arms and drugs”. According to the official, this is why the judicial police has limited travel permits for minors.

* Real names have been withheld for security reasons.

*This article is part of a special investigation by El Espectador and Alianza Rebelde Investiga (Runrun.es, El Pitazo and Tal Cual), and it is being reprinted with permission. You can visit the original stories, which have been nominated to the Gabo journalism award, here.