Text: Ronna Rísquez / Editing: Josefina Salomón / Illustration: Sergio Ortiz Borbolla

It was around 11:00 in the morning when we were driving along kilometre 27 of Troncal 10, the road that connects the largest mining towns in the south of Bolívar state, on the border between Venezuela and Brazil. We had passed Guasipati, El Callao, Tumeremo and El Dorado, and were on our way to Las Claritas, at Kilometre 88.

“Stop that car there, stop that car!” a man shouted with violence and determination at the vehicle where I was travelling with another journalist.

The man was wearing a long-sleeved tshirt with a jungle print. He was carrying a radio around his waist and a small bag across his chest.

“Put the window down, put the window down!” They tell me you are taking pictures of our car here,” he tells us as he listens to the instructions given to him over the radio transmitter.

We all froze. It was true, from the moving vehicle my companion had taken some photos of the mining companies located on the side of the road. But how did this man know? How did he realize?

The man was a “garitero”, as they call people in Venezuela who carry out surveillance and security for armed groups, such as those in El Koki’s mega-gang that I saw in Cota 905, in Caracas, or those surrounding the Tocorón prison. The man who was talking to him on the radio was another garitero stationed at another point on the road, who had seen us taking the photos.

I remembered that I had taken a couple of photos too, but of the landscape in the area, with my phone.

“No! We only took photos of the landscape. Here, here they are,” I said fearfully, as I reached out to show him my phone.

He didn’t take it, he was content looking at the images from the car.

“It’s okay. Don’t panic. You can go on,” he said.

We were silent for a few minutes, managing to recover from the incident after a few kilometres, when we were surprised by a giant billboard announcing our arrival at “Kilometre 88-Las Claritas”. The billboard showed the faces of the most important and symbolic figures of the Bolivarian revolution. From left to right were Simón Bolívar, Hugo Chávez, Nicolás Maduro, Cilia Flores, Diosdado Cabello, Delcy Rodríguez (Vice-President of the Republic), Tareck El Aissami (former Minister of Petroleum), Iris Varela (PSUV deputy and former Minister of Prisons), Tarek Williams Saab (Attorney General), Vladimir Padrino López (Minister of Defence), Ángel Marcano (Governor of Bolívar) and Vicente Rojas (Mayor of Sifontes municipality).

Las Claritas is a dusty place, with streets covered in yellow sand that turns to mud when it mixes with rainwater. It resembled the other mining towns we had seen along the way. But here there was more movement, more shops, more people, more life.

This is not just any mining town. It is the capital of the area where the largest gold deposit in Venezuela, and the fourth largest in the world, is located, with reserves in the order of nearly 1.5 million kilos. It is strategically located between the mining area and the Canaima National Park. It is also the centre of commercial operations in a territory of more than 74 square kilometres of mining activity, where there are also other minerals and precious stones, such as diamonds. And it is on the road to Brazil.

Walking through the town, one is struck by the number and variety of shops. The stores offering mining materials had names such as Valle del Cauca (a Colombian department), La Costeña (as a woman from the Atlantic coast is called in Colombia) and La Azulita (a town in the state of Mérida on the border with Zulia).

Mérida state on the border with Zulia), which gave an idea of the origin of some of the people who settled there.

There was also a shop similar to the one we saw inside the Tocorón prison, with the logos of Balenciaga, Gucci and Nike in the windows, and many men wearing T-shirts like the one worn by the garitero who had stopped us on Troncal 10. We later learned that they were also gariteros, disguised as motorbike taxi drivers, who watched over the whole town. A couple of them remained outside the shop where we stopped to talk to a man. They did nothing, they were just there.

During the governments of Acción Democrática and Copei, between 1958 and 1993, concessions were granted to the Canadian companies Crystallex and Gold Reserve for the exploitation of the mines Las Cristinas and Las Brisas, the two most important mines in Las Claritas, with potential reserves of 7,000 tons of gold according to studies carried out at the time by both transnationals. After several modifications to the conditions, in 2008 the government of Hugo Chávez arbitrarily rescinded the permits of both companies. The companies sued the Venezuelan state, and in 2017 it was announced that they had won the dispute in an international court, so there are already signs of their return to the country, specifically to the Las Claritas area.

Another important milestone is the decree of that nationalized mining and the commercialisation of gold in 2011. By then, the governor of Bolivar state, Francisco Rangel Gómez, had already allowed non-state armed structures to control mining, according to investigations by Transparency International Venezuela. It was from there that the gang of “El Topo” emerged, a criminal who gained notoriety in 2016 with the so-called Tumeremo massacre, when he ordered the murder of 17 miners. Governor Rangel Silva tried to minimise the fact so that it would not be investigated because, apparently, “El Topo” was one of the men he had put in charge of the control of some mines.

Since then, news and reports of massacres and disappearances have been a constant in the south of Bolívar. Violence is part of everyday life, it is the basis of relationships, it is used to resolve disputes and to displace and remove adversaries. This is why the label “blood gold” has become associated with Venezuelan gold.

The outbreak of violence also coincides with another historic milestone: the publication of the decree creating the Orinoco Mining Arc on 24 February 2016.

A report published in 2020 by the Office of the then UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, addressing the Orinoco Mining Arc, identified at least 16 violent incidents or “disputes” in four years – between 2016 and 2020 – that left 149 people dead. Security forces were allegedly involved in some of these incidents. “People working in the Orinoco Mining Arc region of Venezuela are trapped in a generalized context of labour exploitation and high levels of violence by criminal groups that control the mines in the area,” the document says. It adds that the armed groups, known as syndicates, “decide who enters and leaves the mining areas, impose rules, apply cruel physical punishments to those who break those rules, and profit financially from all activities in the mining areas, including by resorting to extortion practices in exchange for protection”.

Since the publication of that report and the pandemic hiatus, the situation has not changed. The most recent report of the UN Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela (an independent body mandated by the UN Human Rights Council to investigate Venezuela), published in September 2022, confirms the allegations human rights violations. “These violations and crimes are perpetrated both by state agents, in particular by the military in charge of security in the mining region, as well as by non-state actors. These non-state actors include criminal groups (known as sindicatos and pranatos) and guerrilla groups in Colombia. The research focuses, though not exclusively, on the period after 2016, the formal creation of the Orinoco Mining Arc”, the research concludes.

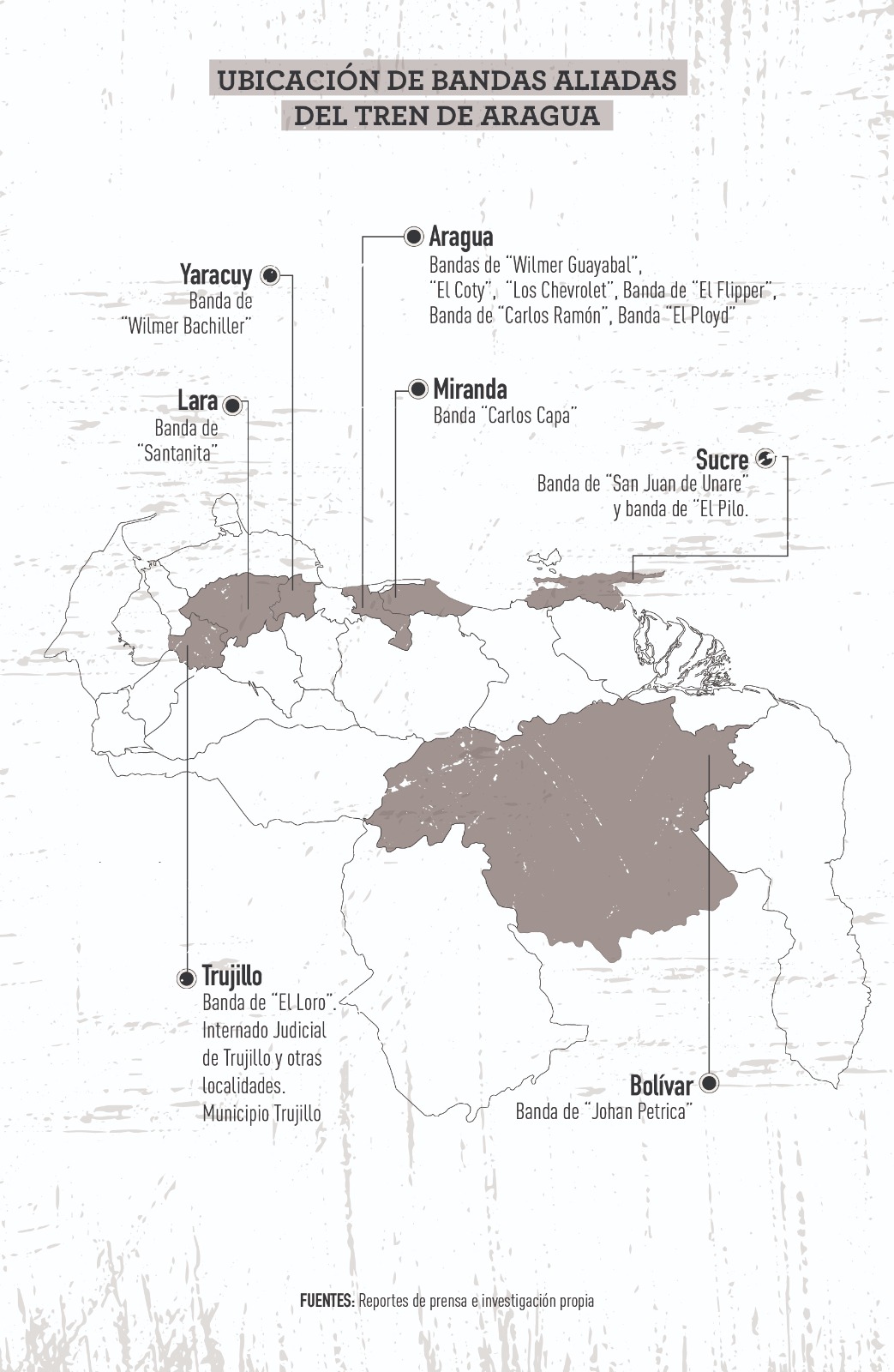

Currently, every major mining town in southern Bolivar is controlled by an armed group: in Guasipati the Tren de Guayana rules; in El Callao there is the El Perú union; in Tumeremo the R Organization dominates; in El Dorado the “Negro Fabio” union rules; and in Las Claritas there was a co-government led by Juan Gabriel Rivas Núñez, alias “Juancho”, and Yohan José Romero (Johan Petrica), one of the three fathers of the Tren de Aragua.

“Juancho” took control of Kilómetro 88 in 2009, with the help of former governor Rangel Gómez and his security secretary, army general Julio César Fuentes Manzulli, according to investigations by Transparency International Venezuela. This criminal reigned alone in this important territory, with the sympathy and complacency of state officials until around the end of 2015, when Johan Petrica arrived to keep him company.

Johan Petrica arrived in the area shortly before the announcement of the creation of the Mining Arc. At first, he did not use his name, he camouflaged himself under the alias “The Old Man” and later became known as “Old Darwing”. Rumour had it that he came from Tocorón, and there was also talk of his links with the Valles del Tuy groups, the two places where most of the people who began to arrive to work in the mines of Las Claritas came from.

For several years, both criminal bosses shared the government in Las Claritas in harmony. But with the departure of Rangel Gómez from the governorship in 2017 and the arrival of Justo Noguera Pietri in office, the mega-gang of Tocorón grew stronger and the balance of power shifted. By 2022, Johan Petrica had finally gained full control of the Kilómetro 88 mines and the town of Las Claritas, after displacing Juancho to other nearby mines. The conquest was no small feat, considering the tradition, leadership and connections Juancho enjoyed. This criminal “change of government” coincided with the arrival of the new governor, elected in November 2021, Ángel Bautista Marcano Castillo.

Johan Petrica’s landing at Kilómetro 88 also coincides with the birth of the Empresa Mixta Ecosocialista Siembra Minera S.A. (Mindeminec), in 2016, which is the result of an alliance between the Corporación Venezolana de Minería (representing the Venezuelan state), with 55 per cent of the shares, and GR Mining Inc (from Barbados), with 45 per cent. The latter shareholder is in fact a subsidiary of the Canadian company Gold Reserve, the same company whose permits were revoked by Chávez and which later won the lawsuit against the Venezuelan state, and is therefore well aware of the value of exploiting the Las Brisas and Las Cristinas mines.

“Here everything works under the figure of alliances. Alliances between government bodies, private companies, institutions and criminals. These alliances are formed with legally constituted companies, and they have links with the Venezuelan Mining Corporation (CVM),” explained Pablo Morales, a local businessman, describing the type of companies similar to Siembra Minera.

Another legal form that is repeated in Las Claritas is that of foundations. These tend to lead on the implementation of social work but also criminal activities including extortion. “Now there are too many foundations here, everything is managed through them,” said Morales, who said they are administered by the crime groups who control the mines and the town. “They manage the fuel, and now they have implemented something like medical insurance. The town’s health service is public, but you have to pay in gold there to be treated and get medicines. You go to the hospital now and there are all those gariteros there guarding their spaces”. The shopkeeper insisted that despite being a government institution, it is controlled by Johan Petrica’s group, assisted by another of the Tocorón leaders, alias “La Fresa”, close to Héctor Guerrero Flores, alias “Niño Guerrero”, head of the Aragua Train in Tocorón prison, who also frequents the village of Las Calritas.

In this mining area, although everyone knows about the Tren de Aragua but few talk about it. The criminal structure is known as “the system” because it controls everything. “Here nobody can bring in cheese or eggs or anything. The gangs have their business where all the people have to buy, they set the prices, they manage a tabulator, nobody can sell under or over”, explained Francisco, a villager who has worked in the mines.

They also manage access to the mines: who works and doesn’t work there and how much there are paid. “They own the mines and the machines. Imagine, they have the best mines. They extract between 30 and 50 kilos of gold a day. Kilos of gold, not sand,” Francisco said.

On average, a kilo of gold fetches $57,000 on international markets. According to that price, if they extract 30 kilos a day, that is equivalent to $1,710,000 a day, more than $51 million a month.

The armed group also obtains other forms of income from the mining activity. “If you have a motorbike, you have to buy a monthly ticket to drive around. So do taxi drivers. That’s what they call here the ‘mecate’, which is like the rope they lift to let you pass”, said Francisco.

Other people we spoke with said that the armed groups don’t own the mines. Their function is to provide security for the mine, take care of the logistics for its operation, control the town and manage the business generated by the mining activity.

Prostitution is also controlled by the “system”, but the dynamics are very particular, said trader Morales. “It’s something that doesn’t make sense. It works like this: the girls come regularly to sell coffee, and they are the coffee sellers, and since they sell coffee, who is going to ban them? However, minors are not allowed to be on the street late at night, but they are 16, 17 and 18 year old girls, who simulate and somehow start in the coffee shop, selling coffee and then some enter what they call ‘the plaza’ (where prostitution takes place)”, according to the shopkeeper.

The other related business is the sale of drugs. “I don’t know to what extent the system controls that. But I do know that there are places where they sell drugs and they are the ones there. Most of the miners use drugs. For example, the ‘bateros’ (those who work with trays fishing for gold), who don’t eat all day and survive thanks to drugs,” said miner Francisco.

On the other hand, the system led by Johan Petrica, by force and sowing fear, has begun to install “vice houses”, where people can use drugs. They have televisions and sleep there. “What happens is that drugs, liquor and brand-name clothes are a business here. If the miner takes a point (measure of gold) or a kilo from you today, he thinks: ‘tomorrow I’ll get more’. And that kilo of gold can be spent on the same day. Then buy a motorbike, buy a car. What I always dreamed of, I buy a pair of headphones, I buy a pair of Jordans (sports shoes). That’s what they buy. What’s more, they’re just trinkets, because here what they sell you are double A (imitation) and triple A Nike shoes, they’re not even original and they sell them for three times the price of an original shoe and people buy them as long as it says Tommy, as long as it says Nike, as long as it shows a brand,” said Francisco.

But those are the miners at the bottom. Because the people who work around this system often travel to Boa Vista and Paracaima in Brazil to shop. “You see the criminals here wearing Balenciaga, Gucci, all original clothes,” the miner said. These bosses of the system only use high-end Toyota vans, and travel without licence plates throughout the region. Many are vehicles stolen in the centre of the country, repowered and modified in workshops run by members of the Tren de Aragua, and then sold in Guayana, where, in addition to being a status symbol, they are a necessity and a kind of signal to avoid being detained by the authorities. “As a policeman, you see a van like that and you don’t stop it, even if it commits an infraction or comes without licence plates. Because you already know that the people in those cars are people from the government, people with connections or criminals. So, if you stop them, you get into trouble”, said the commissioner of the Aragua police, Marcos Pérez.

As for the figure of Johan Petrica, both the shopkeeper and the miner immediately identified him as “El viejo” (the old man) when they saw a photo. “Of course it’s him,” Morales said. “I have seen him many times. He has enormous power and whatever he says is done here. People tremble. But there are also those who say that he is good, that he helps people because he makes pots of soup and gives them out.” In Kilómetro 88, as in San Vicente, schools are controlled by the system. They make a weekly payment of one gold point to teachers, whose formal income (paid by the Venezuelan state) is less than one minimum wage (about seven dollars).

They also organize sports activities and shows with international artists. “The boys from the national indoor football team always come here. The system brings them, and famous reguetoneros. The singers are paid with gold,” said Francisco.

The foundations are also used to collect extortion money in a disguised way. That money is used to fix roads and do other public works. “If they buy X-ray equipment for the hospital or want to open new laboratories, they ask for a contribution of 10 grammes (measure for gold) from the shopkeepers. This way they look good, but we, the traders, are hanging and can’t refuse. The option is to close down and leave”, explained Morales.

It is estimated that at least 5,000 people work for “the system” in Las Claritas. Almost 20 percent of the town. They are its army. “Most of them are people who are not from here. They come from other states, but they also come from Tocorón,” said Morales, the shopkeeper. There are punishment codes for those who break the rules. First, they receive warnings, but if they repeat the offence they are taken with their hands handcuffed behind their backs to a mountainous area from where they do not return. They disappear. The villagers believe it is a place where there are mass graves.

The arsenal of the Tren de Aragua in Las Claritas is large: mainly pistols, rifles of different types and grenades. “The number of weapons here is crazy,” said Francisco.

But Johan Petrica does not lose sight of the horizon. Although he has the Los Rojas, Marruecos and Cuatro Muertos mines under his control, among others, he has dedicated himself to buying real estate to convert it into hotels, in case Canadian or Iranian companies set up in the area.

*This text is part of chapter 6 of the book “El Tren de Aragua, la Banda que revoluciona el crimen organizado en América Latina”, written by our co-founder Ronna Rísquez and published in 2023 with Editorial Dahbar and Editorial Planeta.