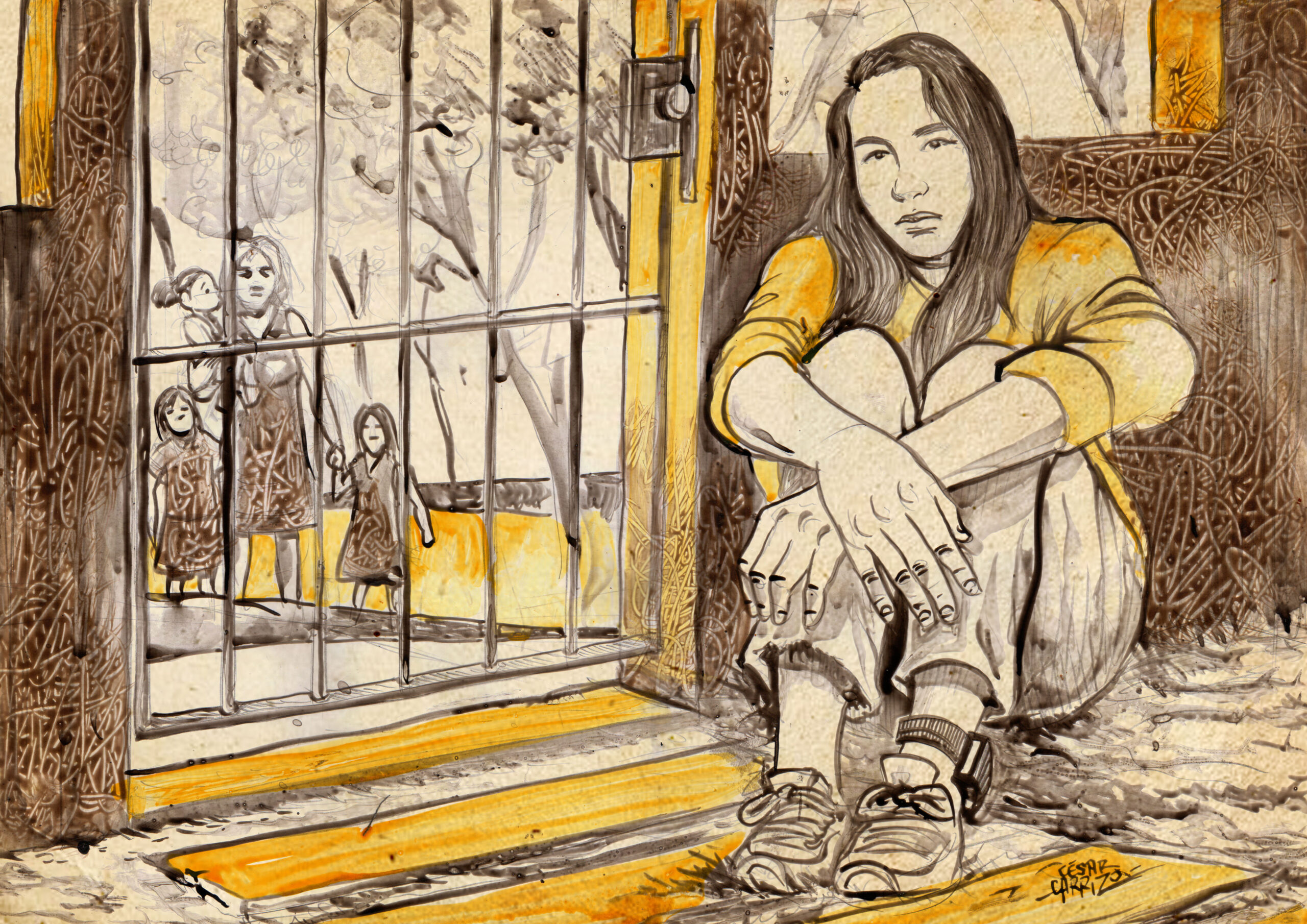

Words: Camila Grigera Naón Illustration: César Carrizo*

On 7 June 2018, Camila Solange Medrano, 30 years old, was arrested as she was leaving a shop in the city of Buenos Aires.

She was accused of having been involved in drug trafficking with her sister-in-law, Noelia Polo Castañeda, with whom she lived.

A court sentenced her to six years in prison for “possession of narcotics for commercial purposes”. She spent five years under house arrest, unable to care for her daughters and help her mother, who suffered from terminal cancer. She was eventually released, after, together with her public defender, Florencia Hegglin, she was able to argue that she had been forced to take part in the crime.

But Medrano had already lost a lot. She had suffered what in legal jargon is called “irreparable harm.”

From a young age, Medrano survived in an environment of violence. At 13, he spent time in a children’s home. By 15, she had already suffered sexual abuse at the hands of family members. Her daughters’ father, Victor Augusto Polo Castañeda, a man almost two decades her senior, began beating her shortly after they met.

By 2015, Medrano already had three daughters and episodes of violence were part of the routine.

Medrano lived with the girls, Polo Castañeda and some of his relatives, including his sister, Noelia. They shared a squat in the neighbourhood of San Cristóbal, in the city of Buenos Aires. Their coexistence was always tense. Medrano says she was controlled by Polo Castañeda, who did everything he could to isolate her from the world.

“He would say to me: ‘you stay here’ and I stayed, I had no communication with my family, my grandmother knew what was going on but I couldn’t call her. He would tell me: ‘You are useless, you don’t know how to cook, you don’t know how to wash clothes,’ and he cheated on me,” Medrano said in the case file.

“I felt that I was worthless in everything I did.”

Medrano always knew she had to get out and get her daughters out of that environment, but the fear of being beaten discouraged her. When she wasn’t working to support them, she made sure she had food made for her partner and kept the house clean.

In March 2018 came the turning point. Noelia was already running a business selling cocaine and marijuana. In the house where Medrano raised her daughters, the coordination, packaging and accounting of the business was carried out. Polo Castañeda delivered the merchandise to the clients.

“He never gave me money for nappies or food,” Medrano said. She says she participated because if she refused, the response was always violent, “problems, blows, fights, or arguments”. It was either that or “I was out on the street,” she recalls. “I was cornered,” she explained.

“I told [Noelia Polo] that I didn’t want to be involved in any of that any more. She replied: “OK, you’re leaving the house then’’. She gathered some belongings and took refuge with her daughters at her grandmother’s house.

She thought the worst was over, but it was not. On 16 February 2018 at six o’clock in the evening, she returned to her ex-partner’s house to get her daughters’ clothes. As soon as she arrived, Polo Castañeda began to insult her, grabbed her by the neck and started hitting her in the chest and head. He then tried to stab her with a knife and set fire to the house with a carafe.

Medrano screamed for help. Two neighbours managed to get the carafe away from Polo Castañeda and take him to the patio. Medrano saw the opportunity and escaped. On the street, she found a patrol car and reported what had happened. Meanwhile, Polo Castañeda came out of the house with two wooden rods about 35 centimetres long with sharp points to attack Medrano. After a brief struggle, the policeman managed to detain the assailant.

Castañeda is currently serving an eight-year sentence for a number of crimes including robbery, drug trafficking and domestic violence.

Medrano had been implicated in the crime of drug micro-trafficking because Victor and Noelia used her mobile phone to develop the logistics of the business. Through wiretaps, the Public Prosecutor’s Office linked them.

It took three and a half years for the justice system to pass the final sentence against Medrano, while she received threats from her ex-partner, who was in prison, and from her relatives who tried to convince her to accept an abbreviated trial, which could benefit them in exchange for her incriminating herself.

Medrano never gave in to the intimidation because she hoped that the judges would understand her motives for participating in the crime. Although her sentence was initially higher, she was acquitted after five years. She managed to prove that her role in the business was not central and that she had acted out of a state of “justifying necessity.”

“Many times, women do not lead the trafficking. This role is often played by men,” explained Hegglin, her lawyer.

“Repeated exposure to coercion conditioned her ability to make decisions. When negative events become chronic and permeate the person and lead to a ‘consequent inability to defend themselves, remaining in abusive relationships’, warned the psychological expertise prepared by Melina Siderakis.

Hegglin has represented other women convicted of small-time trafficking offences. She says securing an acquittal is unusual, as judges tend not look at the cases from a gender perspective or evaluate the vulnerabilities women face.

“They are prosecutors or judges, and they care about what happened, not why. They don’t see the suffering of that person, the suffering of the children, of the families. They don’t see any of those things,” Medrano said. “I think that a person who was not subjected, who was not abused, who was not mistreated, does not do anything like this. Nowadays I would not do it. Victor and his family got to me when I was very young, they trained me,” she reflected.

Medrano served five of the six years she was originally sentenced to under house arrest. She could not leave the house without court permission.

I had to ask for permission to take my daughters to school, to medical check-ups. Sometimes they were granted, sometimes they would forget to tell me,” Medrano lamented.

Nor was she allowed to accompany her mother, who suffered from terminal cancer and died in mid-2020, to medical appointments.

Now that the storm has passed, Medrano lives in Villa Lugano with her three daughters. Since her release, she has returned to high school and works as a domestic worker, while looking for other opportunities that will give her greater job security. She is also training to become a nurse.

Reflecting on the role that vulnerable women play in the drug distribution chain, she says: “We are not talking about murder or rape. We are talking about something that is a crime and that I wouldn’t recommend anyone to do, but they should look at the background, at what happened in that person’s life to lead them to what they did.”

* Camila Grigera Naón wrote this report with the support of the Federal Network of Judicial Journalism. The piece is part of the investigation ‘Women and drug micro-trafficking, a blind spot in the Argentinean justice system’. It is a project of the Network supported by the Fund for Research and New Narratives on Drugs (FINND) of the Gabo Foundation and the Open Society Foundations.