Text: Team In.visibles

Luis Eduardo Roberto Hernández, a motorbike taxi driver from Upata, Bolívar state, in Venezuela’s mining region, died on Tuesday 30 July from a bullet wound to the face while taking part in demonstrations against the results of the presidential election, which contested results proclaimed Nicolás Maduro as the winner.

“My son was killed by the colectivos,” his father, Luis Roberto, told reporters from El Pitazo. He says the doctors who treated the 19-year-old told him that his death had been caused by a bullet. Government officials, however, tried to spin the story by saying that Luis Eduardo had died from a rock injury.

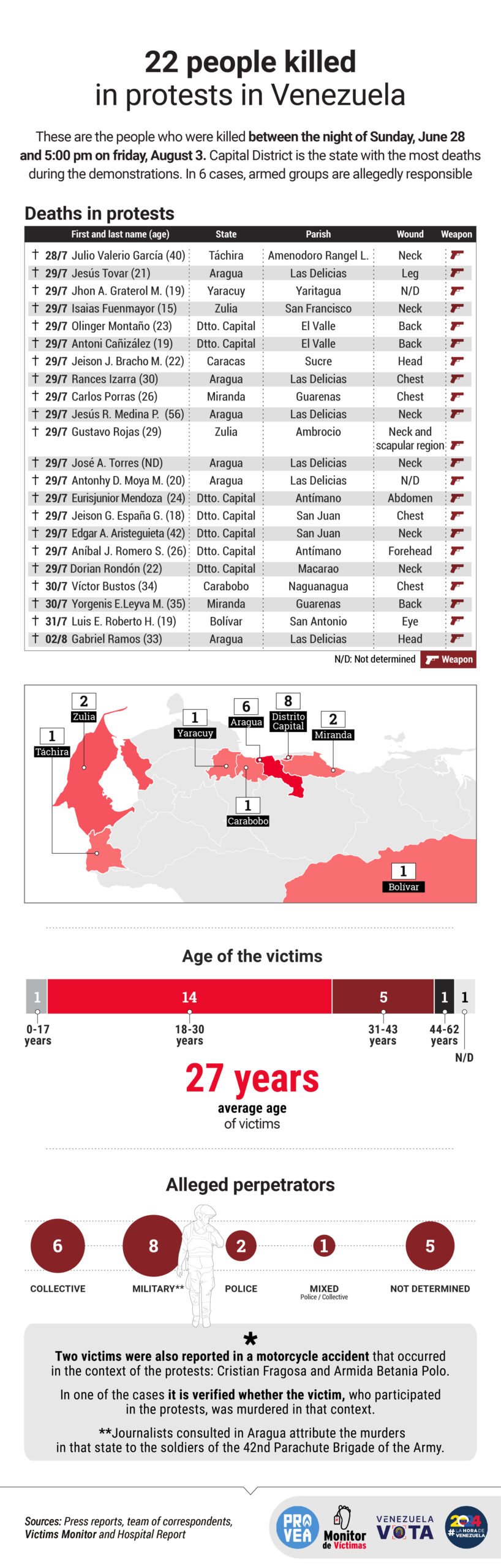

In just three days – between 28 and 30 July 2024 – the organisations Monitor de Víctimas and Provea recorded that at least 22 people died during hundreds of protests around Venezuela, after the National Electoral Council (Consejo Nacional Electoral – CNE) said Maduro had won 51.2 per cent of the vote, compared to 44.2 per cent for opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia.

The Attorney General, Tarek Williams Saab, said that in the same period 1,062 other people had been arrested (civil society organisations have verified 939 cases). In addition, dozens of cases of threats and persecution of social leaders, political activists and journalists have been reported, in a context of high criminalisation of demonstrations.

The opposition says that according to its own count, they won with 70 per cent of the vote, against Maduro’s 30 per cent.

At the heart of the debate is the process of verifying the tallies, which the government has yet to publish, even after repeated requests from governments considered allies in the region and independent observers. Instead, it has accused the opposition of fomenting a coup d’état and expelled diplomats from countries that questioned the election results. The party of Maria Corina Machado, an opposition leader who was barred from the election contest, says her offices were attacked by masked assailants. Machado has moved to a safe house, she says is afraid.

Even before the wave of protests, tension had marked an electoral contest that many defined as historic, because of the opposition coalition’s real possibility of coming to power through the ballot box after 25 years of Chavista rule.

While the Venezuelan economy experienced a better period during the first years of Hugo Chávez’s administration, accompanied by a boom in oil prices (Venezuela has some of the world’s largest oil reserves), things changed drastically around 2013, when Maduro became president. At its worst, the country reached a record inflation of 130,000%, one of the causes of a complex humanitarian emergency, evidenced by the endless lines of people looking for food and the explosion of migration. More than 7.7 million people have left Venezuela since 2014.

In the midst of all this, Venezuela became a haven for corruption and organised crime. A variety of armed groups proliferated, ranging from mega-gangs and pranes (organizations that operate from prisons)- born in the country’s prisons – to armed colectivos, a sort of paramilitary groups claiming to seek to defend Hugo Chávez’s revolution. These structures quickly developed, engaged in criminal markets such as drug micro-trafficking, extortion, kidnapping, human trafficking and smuggling, illegal mining and contract killings, among others, and found ways to capitalise on the oil price boom.

The colectivos, which do not operate as a national unit but have a presence in the state, managed to build a criminal market based on the territorial control and governance they began to exercise in the communities where they operated.

They developed businesses related to the commercialisation of food, the control of service stations for subsidised fuel – which is often in short supply in Venezuela -, the administration of gas supplies, foreign exchange operations, and the mining and commercialisation of gold. Many focused on extortion in exchange for “security”, drug micro-trafficking and selective assassinations.

While it is not possible to say precisely how many people are members of the colectivos, experts say they use more violence than other organisations, in part because of the weapons they have access to.

Researchers have documented the presence of some 100 collectives in at least 14 of Venezuela’s 23 states. The strongest and best known are: Tres Raíces, La Piedrita, Alexis Vive (23 de Enero), Catedral, Cupaz (Lara, Portuguesa and Yaracuy), Red Elco (Lara), Frente 5 de Marzo (Apure), Cara Al Río (Miranda), Hijos de Bolívar and Coco Secos (Sucre).

The huge turnaround for the colectivos began in 2021, when they managed to occupy the territories and criminal markets that some mega-gangs had left behind, after their members began to be arrested or were killed in alledged clashed with the police, and their groups reorganized in Venezuela or abroad.

In these areas, in addition to controlling illicit activities, the collectives also exercise an important and very sophisticated territorial control, and impose criminal governance. They also play an important role in the political repression of the opposition and have long been considered the armed wing of the Bolivarian revolution.

The colectivos, for example, accompanied the Operations for the Liberation and Protection of the People (OLP) in the fight against criminal gangs, and acted alongside the security forces in the repression of protests in 2014 and 2017, when they were accused of 28 killings. In the most critical moments faced by his government, Maduro called on the colectivos to support him and claimed to be their biggest supporter. During the protests this week, the colectivos are believed to be behind at least seven deaths.

Residents of areas where they operate said that the colectivos have taken over the role of the state, including in the administration of public services, food distribution and access to health services.

An incident on 4 February in Petare, in the Sucre municipality of Miranda state, highlighted the relationship between the colectivos and the government of Nicolás Maduro.

A group of 14 alleged members of a colectivo called “Cara Al Río” were detained by the police when they were plundering a stolen vehicle. Inhabitants of the community reported the alleged robbery and said that the criminals were hiding in a shed in the area. When the security forces arrived, they allegedly found the members of the colectivo with the vehicle and a number of firearms.

Hours later, members of the colectivo, most of them hooded and armed, staged a protest on a major avenue to demand the release of their comrades and forced the transporters to block the road.

The deputy minister of the Integrated Police and Citizen Security System, Major General Elio Estrada, eventually ordered the release of the detainees and cancelled the proceedings against them. He also met with the collective and promised them that this type of situation would not happen again.

Estrada Paredes, who also serves as vice minister of the Integrated Police System, also ordered the return of the eight weapons they were carrying at the time of their arrest, four motorbikes, a vehicle and a tow truck, according to media reports.

When confronted with figures illustrating the gravity of the situation in Venezuela, Maduro says the worst is over. He forecasts economic growth. He says the new Venezuela is coming.

In the marginalised neighbourhoods outside Caracas, and more in the rest of the country, the testimonies tell a different story.

They speak of lack of food, insufficient salaries, extortion, the wide availability of weapons and fear.

In the context of the protests, the inhabitants of the peripheral communities say that at night they hear gunfire and that the colectivos go out on patrol alongside the National Police, whose numbers are declining, partly because many of their members have migrated to other countries.

Meanwhile, the big question is what will be the future of these organisations that have amassed so much power over the past decades be if they ever cease to have a monopoly of force, or state connivance. The answer is complex.

Maduro is already promoting a civic-military-police union, which opens up the possibility that members of these paramilitary organisations could remain within the security forces. This is problematic for many reasons, including for the pursuit of justice for crimes committed during the repression – the involvement of these civilians makes it difficult to establish accountability and attribute sanctions.

Whatever happens, what is clear is that the power that these groups have amassed is such that they have become a key player on Venezuela’s complex chessboard, one with which any future government will need to negotiate and seek agreements. This may also generate a potential new rearrangement of the criminal landscape, with all the challenges that this will generate.